Unmasked

How a Story City man finally faced his mental health crisis and in doing so, brought a new focus to his life.

By Steve Sullivan

Jeff Crisman was the last speaker that Sunday in November at the Harvest Evangelical Free Church in Story City.

He wasn’t there to deliver a sermon or recite Bible passages, though he knows many by heart. He was there to share an intensely personal story. It was almost a confession really, about how he had silently coped with mental illness. Crisman talked about how he had come perilously close to ending his life. He shared how he relied on his faith to get him through his darkest days but came to realize he needed something more. He explained how someone well known to many in Ames though who he had never met convinced him to get help. Ultimately, Crisman told a story about how he found a renewed purpose to keep on living.

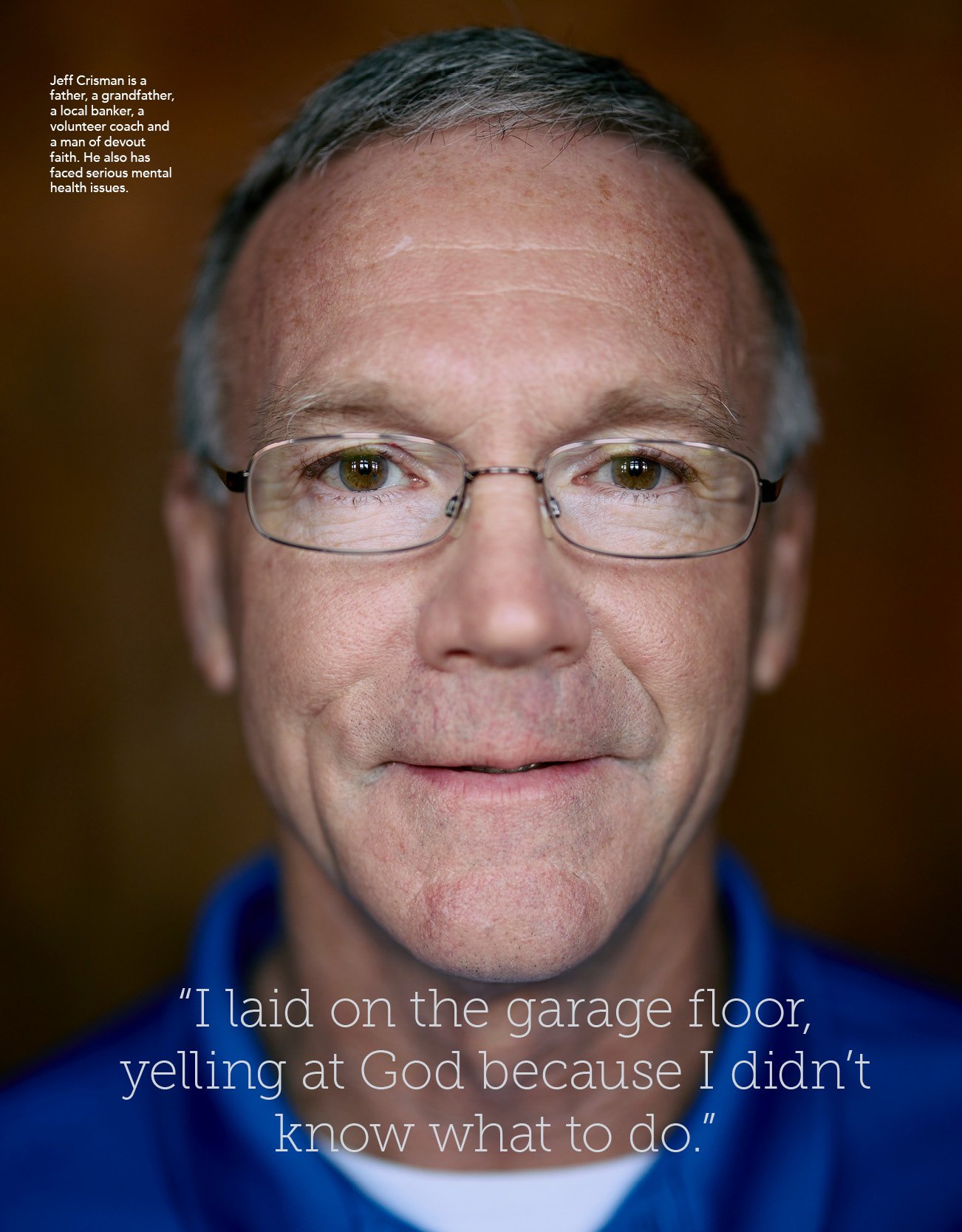

This wasn’t easy. Crisman admits that he had been hiding behind a mask for much of his life. That mask hid a lot of pain. Crisman is a longtime banker in Story City. His customers have his cellphone number and are welcome to call him anytime. He’s been a volunteer football coach and organized a Christian athlete group. He’s served on Story City’s city council. A former college football player, he’s a physically fit father and grandfather. He’s a typical, upstanding Midwesterner … and guys like that don’t have mental health problems, right?

Wrong.

Mask

Crisman’s mask started slipping in August of 2021. He’d been dealing with depression for years. On many mornings, he had to drag himself out of bed because people were counting on him. He grew up in a big family with limited resources and played sports. He abided by the philosophy of “suck it up.”

But a crisis in his personal life finally pushed him to a breaking point. He woke up in the middle of the night, a darkness weighing on him. He wrote a suicide note and went to the garage with a shotgun he hadn’t used in years and two shells.

“I laid on the garage floor, yelling at God because I didn’t know what to do,” he said.

The “suck it up” kicked in though and Crisman pulled himself together, got himself ready for work and went to the bank.

“You’d never know I have a problem,” said Crisman. “I smile and say everything is fine. I wear a really good mask. I can hide anything.”

He couldn’t avoid going further into the dark place though. More than once he found himself in his closed garage with the car engine running. It seemed like the only way to end the pain.

He was rescued from these moments by his faith, or a timely text from a friend. While at the home of a couple he’s known for years, Crisman opened up about what he’d been going through. We know someone, his friends told him, someone who might talk to you.

Fennelly

They were referring to Lyndsey Fennelly, who became a mental health advocate after going public with her own struggles. Crisman didn’t know who she was but reached out and had a phone conversation on a Saturday. Crisman was parked at local big box store, sitting in the car where he had pondered suicide so many times. This time, though, he was receiving a life line.

“I take great pride in being a mental health experiencer, but I’m not an expert,” Fennelly said. “From Jeff’s tone I could sense nervousness, embarrassment and overwhelming sadness. What I sensed most though was helplessness.”

He remained resistant to getting help. He had his faith. He was reading Pastor Rick Warren’s “The Purpose Driven Life.” He could suck it up.

Crisman had a sense of shame about “stepping a foot in that hospital,” Fennelly said. “I tried to relate to him about the times I had been there and the life I lead very publicly now. I wanted him to know what I knew when I left the hospital, that it was a place of hope and health and that a better version of Jeff Crisman was available within those walls.”

“I told her what I was going through, and she told me her story,” said Crisman. “She seemed to understand how I felt, and I will never forget her telling me that there was a word that she had to learn. That word was ‘surrender.’”

Inspired by Fennelly, Crisman surrendered to his crisis and went to the Emergency Department at Mary Greeley.

Treatment

“It’s a little embarrassing to say I was scared, but I was,” he admits. “Lyndsey said that they would take care of me, and they did.”

He asked a nurse “why now?” He’d been managing his issues for so long, why did he fall apart now? Your brain just couldn’t do it anymore, he was told.

“Mental health is easily stigmatized because a person’s mental toughness can be put in question. It’s easy for a person struggling with their mental health to question themselves and assume fault for thinking and feeling the way they do,” said Dr. Anna Statz, a psychiatrist with Mary Greeley’s outpatient Behavioral Health Clinic. “We are also conditioned to want people to think the best of us, and the ‘best’ is to be joyful, energetic, care-free, capable. This is often the mask that’s hidden behind. If the mask were to come off, other people might find out the ‘truth,’ which is terrifying for people.”

Statz added that “it takes a significant amount of energy to keep this mask on day after day because it’s not in-sync with how a person feels inside. It doesn’t flow, it’s not spontaneous. It’s calculating and difficult. Soon this mental energy will burn out, particularly for a person struggling with a mental illness, when energy reserves are already low. A significant stressor or accumulation of stressors can burn up the mental energy reserve, and this can become a dangerous and vulnerable time for a person. They may feel ‘out of control’ and behave in ways fueled by the emotional intensity that has been pent up all that time, which can sometimes lead to things like suicide attempts or self-harm, or hopefully, a reach for help.”

Crisman was placed in a designated area in the ED for Behavioral Health patients and put on a 48-hour hold. The hospital’s inpatient unit was full and Crisman was told he would have to be transferred to a facility in Council Bluffs.

Crisman protested: “Lyndsey Fennelly told me this is where I need to be.”

Fortunately, a bed became available and Crisman arrived at Mary Greeley’s inpatient Behavioral Health unit with his Bible, journal, and his copy of “The Purpose Driven Life.” All those items, per standard procedure, were taken from him.

“So why are you here today?” he was asked by a nurse on the unit.

He told the nurse everything and about the support he’d received from Fennelly. “We love Lyndsey,” was the nurse’s response. He knew he was in the right place.

His blood pressure was high, and a decision was made to let Crisman have his Bible, which helped.

“I went from absolutely terrified to almost numb,” he said. “But I told myself, ‘This is what it is now. I’m here.”’

Staff checked on him regularly. He was able to watch church services online. He met with therapists and staff. He participated in group meetings. When discussing medications, he expressed concern about being a “vegetable or a zombie.”

That won’t happen he was assured. “Jeff will be Jeff,” he was told.

“There was no judgement. They listened to me, and they cared,” he said.

He was in the hospital for five days. He learned how to recognize feelings of depression and to use coping exercises.

Relapse

He wasn’t totally in the clear yet, though. Despite everything he’s done, the darkness crept in again. On a day in late October, he was in his garage, with the car running. He had a pillow and a blanket. He listened to Bible verses over his phone. He prayed for God’s forgiveness.

“It was about 7:15 a.m. when I started the engine,” he said. “I woke up at almost 11. I was still here. Three and half hours and I was still there. I didn’t know why.”

He realized why a few days later when a friend texted with a request for prayers for his teenage daughter, who was in the hospital after taking an overdose of antidepressant pills. She survived but was being sent to a facility far from home and didn’t want to go. Crisman reached out to her.

A New Purpose

“I asked if she felt alone, which she did. I told her that I did too, and my marriage had ended and that I had tried to hurt myself,” he said., “I told her that God loves her and wants her here for a reason. I urged her to go the hospital and get help.”

She relented and went. Crisman continues to check in on the young woman and help with her struggles. Crisman had found a new purpose: To help young people suffering from mental illness.

He’s reached out to families who have lost children to suicide. He volunteers with National Alliance on Mental Health (NAMI) Central Iowa. He gets welcome support from friends and colleagues. After speaking at the church that Sunday, he got a note from someone in the audience who struggled with depression and suicidal thoughts while a teen and didn’t get help until they were a young adult. “I wish I had someone as a teenager that would’ve helped me,” the person wrote.

“Many times, what leads to healing and inner peace for folks struggling with mental health is to realize they aren’t the only ones dealing with these issues. Normalizing experiences gives permission for a person to display their authentic selves, especially when it’s imperfect, and when one person can display their authentic selves, it allows others the opportunity to do the same,” said Statz. “This compassionate and supportive community that can be created, in a place like NAMI for instance, is an imperative piece of a person’s mental health stability. With his perspective, a person like Jeff can join a community like this and create these strong supportive relationships, but also he can offer his experience to help normalize someone else’s mental health experience when they are struggling.”

Crisman no longer wants to hurt himself. He takes medication and continues his treatment through Mary Greeley’s outpatient Behavioral Health Clinic. He copes through physical activity and finds peace in baking cookies. He often brings them to Mary Greeley to share with the staff who helped him through the darkest moments of his life. His faith is as strong as ever.

“We don’t know the plan that God has for us,” he said. “If I hadn’t faced the kind of crisis I did, I might never have gone to the hospital to get help. If I didn’t have these friends who I’ve known for years, I might never have met Lyndsey Fennelly. God gives us community.”

New Behavioral Health Unit Coming to Mary Greeley

Next year, Mary Greeley Medical Center will open a new adult inpatient Behavioral Health unit.

The new unit will increase capacity from 18 patients to 24 and offer a modern treatment environment. The new unit will be complemented by several other mental health-focused services at Mary Greeley, including our growing Outpatient Behavioral Health Clinic, which provides patients with therapy and medication management.

Our Emergency Department offers crisis assessments and referrals 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The department treats both adult and adolescent patients with mental illness. The Transitional Living Center – Subacute Care facility provides subacute care in a home-like setting for individuals with symptoms that keep them from being able to live independently.

Mary Greeley’s behavioral health services are provided by a coordinated, multidisciplinary team that includes:

• Board-certified Psychiatrists

• Physician Assistants

• Psychiatric & Mental Health Nurse Practitioners

• Registered Nurses

• Licensed Mental Health Therapists

• Substance Abuse Counselors

• Psychiatric Assistants

• Licensed Social Workers

For more information on how you can support our vision for Mental Health Services in our community, visit www.mgmc.org/foundation/mentalhealth.